When you’re running a clinical trial, not every bad reaction needs to be reported right away. But knowing the difference between a serious adverse event and a non-serious one can mean the difference between protecting a patient and wasting weeks on paperwork that doesn’t matter.

What’s the real difference between serious and non-serious?

It’s not about how bad the symptoms feel. A pounding headache might be severe, but if it goes away with ibuprofen and doesn’t land someone in the hospital, it’s not serious. Serious isn’t about intensity-it’s about outcome.

The FDA and ICH define a serious adverse event (SAE) by six specific outcomes:

- Death

- Life-threatening condition

- Requires hospitalization or extends an existing hospital stay

- Results in permanent disability or significant loss of function

- Causes a birth defect

- Requires medical intervention to prevent one of the above

If none of those apply? It’s non-serious. Even if the patient was in agony for three days. Even if they needed a prescription. Even if they missed work. None of that makes it serious. Only the outcome does.

This distinction isn’t just bureaucratic-it’s practical. In 2022, the FDA’s Sentinel system received over 14.7 million adverse event reports. Only 18.3% of them met the seriousness criteria. The rest? Noise. And that noise is slowing down real safety signals.

When do you have to report a serious event?

If an SAE happens, the clock starts ticking the moment the investigator learns about it. Not when the paperwork is filled out. Not when the team has a meeting. Right then.

Investigators must report SAEs to the trial sponsor within 24 hours. No exceptions. Whether it’s clearly linked to the drug or not. Whether it’s expected or unexpected. Within one day.

The sponsor then has to tell the FDA:

- 7 calendar days for life-threatening events

- 15 calendar days for all other serious events

And if it’s unexpected? That triggers even stricter rules. Unexpected means it wasn’t listed in the study protocol or investigator brochure. Those get flagged immediately.

For the Institutional Review Board (IRB), most sites require SAEs to be reported within 7 days. But non-serious events? They often don’t go to the IRB at all-unless the protocol says otherwise. Many sites only report them during routine reviews, like every three or six months.

Why do people keep mixing up severity and seriousness?

Because it’s easy. And because it’s tempting.

When a patient says, “I’ve never felt this bad,” it’s natural to think, “This is serious.” But that’s not how the rules work. A severe cough isn’t serious unless it leads to pneumonia requiring ICU admission. A severe anxiety attack isn’t serious unless it causes self-harm or hospitalization.

A 2020 report from the Clinical Trials Transformation Initiative found that nearly 37% of adverse events submitted to IRBs as “serious” didn’t actually meet the criteria. That’s almost four out of every ten reports that were wrong.

At one major cancer research network, 32% of SAE reports had to be corrected because of misclassification. That’s over 18 hours a week of staff time spent fixing mistakes.

And it’s worse in oncology. Why? Because patients are already sick. A drop in white blood cells? Common. But if it doesn’t lead to infection, fever, or hospitalization? It’s not serious. Yet many still report it as such.

How do you get it right every time?

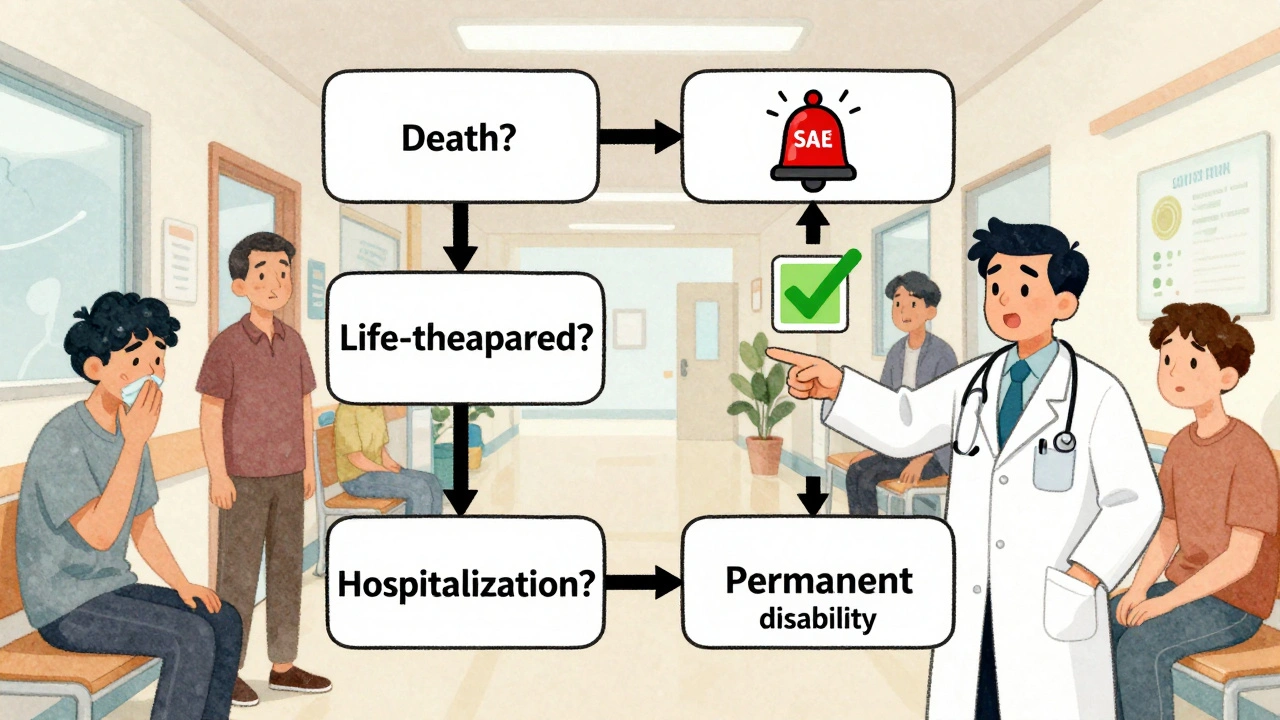

Use the decision tree. It’s simple. Ask these four questions:

- Did the event cause death?

- Was it life-threatening?

- Did it require hospitalization or extend an existing stay?

- Did it cause permanent disability or significant incapacity?

If the answer is yes to any of these? It’s serious. Report it. Now.

If the answer is no to all? It’s non-serious. Document it in the Case Report Form (CRF), note the severity (mild, moderate, severe), and move on. Save the emergency reporting for what actually matters.

Most sites now use the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 5.0 to grade severity-but they keep seriousness separate. Severity tells you how bad it felt. Seriousness tells you if the patient’s life or function changed.

What happens if you get it wrong?

Under-reporting SAEs? That’s dangerous. You could miss a pattern that kills patients in future trials.

Over-reporting? That’s just as bad. It floods regulators with noise. The FDA’s Dr. Janet Woodcock said in 2022 that the system is “overwhelmed by non-serious events reported as serious,” which makes it harder to spot real threats.

At the University of California, San Francisco, over 40% of AE reports in 2022 needed clarification because the seriousness wasn’t clear. That meant delays. That meant investigators waiting weeks for feedback. That meant trials stalled.

And it costs money. Deloitte estimated in 2023 that 62.7% of adverse event reporting costs come from misclassified non-serious events. That’s billions wasted annually.

What’s changing in 2025?

The rules are getting smarter.

The FDA’s 2023 draft guidance proposes tiered reporting timelines based on severity within serious events. A life-threatening event with high severity? Faster report. A serious event with low severity? Slightly longer window.

The European Union’s Clinical Trials Regulation, fully in effect since 2022, now uses the same seriousness definition across all 27 member states. That’s cut cross-border confusion by over a third.

And AI is stepping in. Automated tools now classify seriousness correctly 89.7% of the time-better than humans. But they still need a human to confirm. That’s the new standard: AI flags, human decides.

By 2025, the ICH’s E2B(R4) system will be fully live. That means every adverse event report will be sent electronically in the same format, worldwide. No more fax machines. No more paper forms. Just clean, structured data.

What should you do today?

1. Train your team. Every single person who handles adverse events-coordinators, nurses, data managers-must know the six criteria. Annual training isn’t optional. It’s required by ICH E6(R2).

2. Use the decision tree. Print it. Post it. Put it in your EMR. Make it the first thing you check when an event is reported.

3. Don’t rely on intuition. If a patient says “I felt like I was going to die,” that’s not proof. Did they get intubated? Was their blood pressure crashing? Did they need ICU care? That’s what matters.

4. Use CTCAE for severity. Use ICH/FDA criteria for seriousness. Keep them separate.

5. Audit your reports. Every quarter, pull 10 random SAE reports. Ask: Did this really meet the criteria? If not, why? Fix the process.

Reporting isn’t about being thorough. It’s about being accurate. The goal isn’t to report everything. The goal is to report what changes lives-and to leave the rest out so the real signals can be heard.

Is a severe headache a serious adverse event?

No, not by itself. A severe headache is a high-intensity symptom, but it’s only serious if it leads to hospitalization, brain hemorrhage, stroke, or permanent neurological damage. If the patient took aspirin and went home, it’s non-serious-even if it was the worst headache of their life.

Do I need to report every side effect in a clinical trial?

No. Only serious adverse events require immediate reporting. Non-serious events should be documented in the Case Report Form (CRF) and reported according to the study protocol-usually monthly or quarterly. Over-reporting non-serious events slows down safety reviews and hides real dangers.

What if I’m not sure whether an event is serious?

When in doubt, report it as serious and mark it as ‘under review.’ Then consult your safety officer or IRB. It’s better to report and later find out it wasn’t serious than to miss a real safety signal. But don’t just guess-use the six outcome criteria. If none apply, it’s not serious.

Can a non-serious event become serious later?

Yes. If a patient develops a rash that starts as mild but then leads to hospitalization for toxic epidermal necrolysis, the original event becomes serious retroactively. You must update your report with new information. Safety monitoring is ongoing-events can evolve.

Why do some trials report non-serious events to the IRB?

Some protocols require it for transparency, especially if the event is common or unexpected in that population. But it’s not required by regulation. The IRB’s main job is to protect participants from harm-so they focus on serious events. Non-serious reports to the IRB are usually protocol-specific, not rule-based.

Are psychiatric events treated differently?

No. A panic attack or severe depression is only serious if it leads to suicide attempt, hospitalization, or permanent disability. Many researchers mistakenly report ‘severe anxiety’ as serious-but unless it results in one of the six outcomes, it’s not. The NIH’s 2023 update clarified this: emergency room visits alone don’t qualify unless they meet other criteria.

What’s the most common mistake in reporting?

Confusing severity with seriousness. People see ‘severe pain’ or ‘severe nausea’ and assume it’s serious. But severity is about intensity. Seriousness is about outcome. A patient can have severe nausea and still go home the same day-that’s non-serious. That’s the mistake 89% of clinical staff make at least once.

9 Comments

Graham Abbas

December 9, 2025 at 02:32 AM

There’s a deeper philosophical tension here, isn’t there? We’re trying to reduce human suffering to binary outcomes-life or death, hospitalized or not. But what about the quiet, invisible suffering? The person who can’t hold their child because of chronic pain but doesn’t meet the "serious" threshold? The system is built for survival, not healing. Maybe we need to ask not just "Is this serious?" but "Does this matter to the person?" And if it matters, shouldn’t that count too?

Elliot Barrett

December 10, 2025 at 21:29 PM

This whole post is just corporate fluff dressed up as wisdom. Everyone knows the rules. The problem is no one follows them. Nurses are overworked, coordinators are burnt out, and the "decision tree" is buried in a PDF no one opens. You think training will fix it? Nah. Fix the staffing. Fix the workflow. Stop pretending a checklist solves a broken system.

Tejas Bubane

December 12, 2025 at 10:22 AM

Let’s be real. The FDA’s 18.3% statistic is misleading because most sites are still using CTCAE v4. The v5.0 update changed how they grade certain events-especially in oncology. But nobody updates their SOPs. I’ve seen sites report "grade 3 neutropenia" as serious because they don’t know it’s only serious if febrile. This isn’t about criteria-it’s about incompetence disguised as bureaucracy.

Lisa Whitesel

December 12, 2025 at 13:51 PM

If you report everything you’re a paranoid fool if you report nothing you’re a murderer there is no middle ground and if you think you can use intuition you are lying to yourself and everyone else

Larry Lieberman

December 12, 2025 at 19:53 PM

AI is now 89.7% accurate at flagging SAEs?? 🤯 That’s wild. But also kinda terrifying. Imagine an algorithm saying "this panic attack isn’t serious" while someone’s crying in a corner. We still need humans to feel the weight of this stuff. AI flags. Humans hold the truth. 💔

Richard Eite

December 13, 2025 at 12:58 PM

America still uses fax machines in 2025? Get with the program. This is why the US is behind Europe. EU already unified the rules. We’re still arguing over whether a headache counts. Fix your systems not your excuses

Katherine Chan

December 15, 2025 at 12:48 PM

I love how this post doesn’t just tell you what to do but why it matters. It’s not about rules-it’s about making space for real people to heal without drowning in paperwork. I’ve seen trials fail because we missed a signal buried in noise. Thank you for reminding us to listen-not just log

Ronald Ezamaru

December 16, 2025 at 09:06 AM

I’ve worked in clinical trials across 7 countries. The biggest issue isn’t the rules-it’s the culture. In India, we report everything because we fear liability. In Germany, we’re hyper-precise. In the US, we’re overwhelmed. The real solution? Global training standards. Not just tech. Not just checklists. Real human-to-human education. Share stories. Talk about the patient who got lost in the system. That’s how you change behavior.

Kathy Haverly

December 8, 2025 at 06:14 AM

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me a patient can have a migraine so bad they vomit for 12 hours, miss work, and can’t look at light, but if they don’t end up in the ER, it’s just "noise"? That’s not practical, that’s cruel. You’re dehumanizing pain to save paperwork. I’ve seen people dismissed because their suffering didn’t fit your checklist. This isn’t efficiency-it’s systemic indifference.