What Exactly Is Hypoglycemia?

Hypoglycemia is a condition where blood glucose drops below 70 mg/dL (3.9 mmol/L), most commonly in people with diabetes who take insulin or certain oral medications. It’s not just a minor inconvenience-it’s a medical event that can lead to confusion, seizures, or even unconsciousness if not treated quickly. The body needs glucose to function, especially the brain. When levels fall too low, the brain starts to shut down. This isn’t theoretical. In the U.S., over 100,000 emergency visits each year are due to severe hypoglycemia.

For people without diabetes, hypoglycemia is rare and usually tied to other health issues like insulin-producing tumors (insulinoma) or after gastric bypass surgery. But for those managing diabetes, it’s a daily risk. About 47% of people with Type 1 diabetes experience at least one episode per year. For those on insulin with Type 2, it’s around one in three. The problem isn’t getting worse-it’s getting smarter. New tools like continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) help catch lows before they happen, but they’re not foolproof.

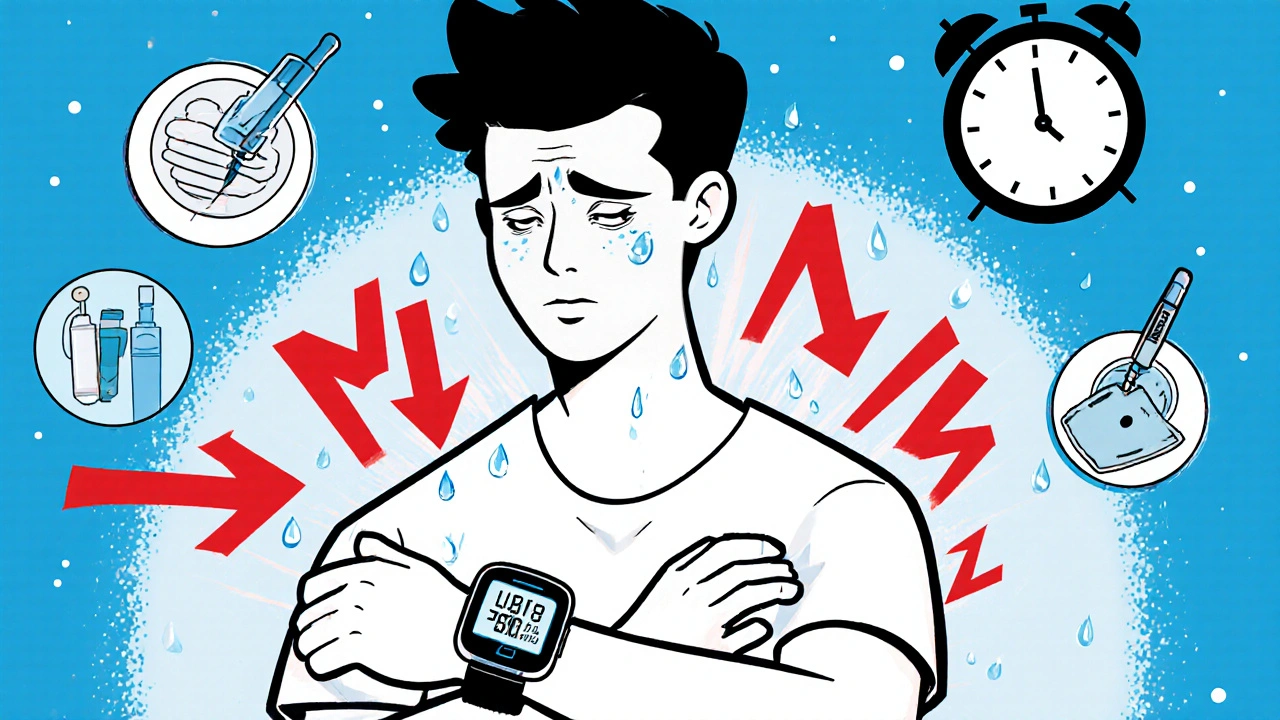

How Do You Know When Your Blood Sugar Is Low?

There are two types of symptoms: physical and mental. The physical ones come from your body’s stress response-your adrenal glands release adrenaline to try to raise your blood sugar. That’s why you might feel shaky, sweaty, or have a racing heart. These signs usually show up when glucose drops below 70 mg/dL. But here’s the catch: not everyone feels them the same way.

Some people get a pounding heart and cold sweat. Others feel dizzy or hungry. Then there are the brain-related symptoms-blurred vision, trouble concentrating, slurred speech, or sudden irritability. These happen when glucose falls below 60 mg/dL. At 50 mg/dL or lower, you might start acting drunk: stumbling, confused, unable to speak clearly. Below 45 mg/dL, seizures or unconsciousness can occur. That’s when someone else has to step in.

One of the scariest things about hypoglycemia is unawareness. After years of frequent lows, some people stop feeling the warning signs. This happens in about 25% of long-term Type 1 diabetes patients. They wake up with a headache or find their CGM flashing 38 mg/dL-no shaking, no sweating, no warning. That’s why checking your blood sugar regularly-even when you feel fine-isn’t optional.

What Causes Low Blood Sugar?

Most hypoglycemia in diabetics isn’t random. It’s caused by a mismatch between medication, food, and activity. Here’s how it breaks down:

- Too much insulin or medication (73% of cases): Taking your usual dose but eating less, or injecting too much by accident.

- Not enough carbs (19%): Skipping a meal, eating too little, or miscalculating your carb intake.

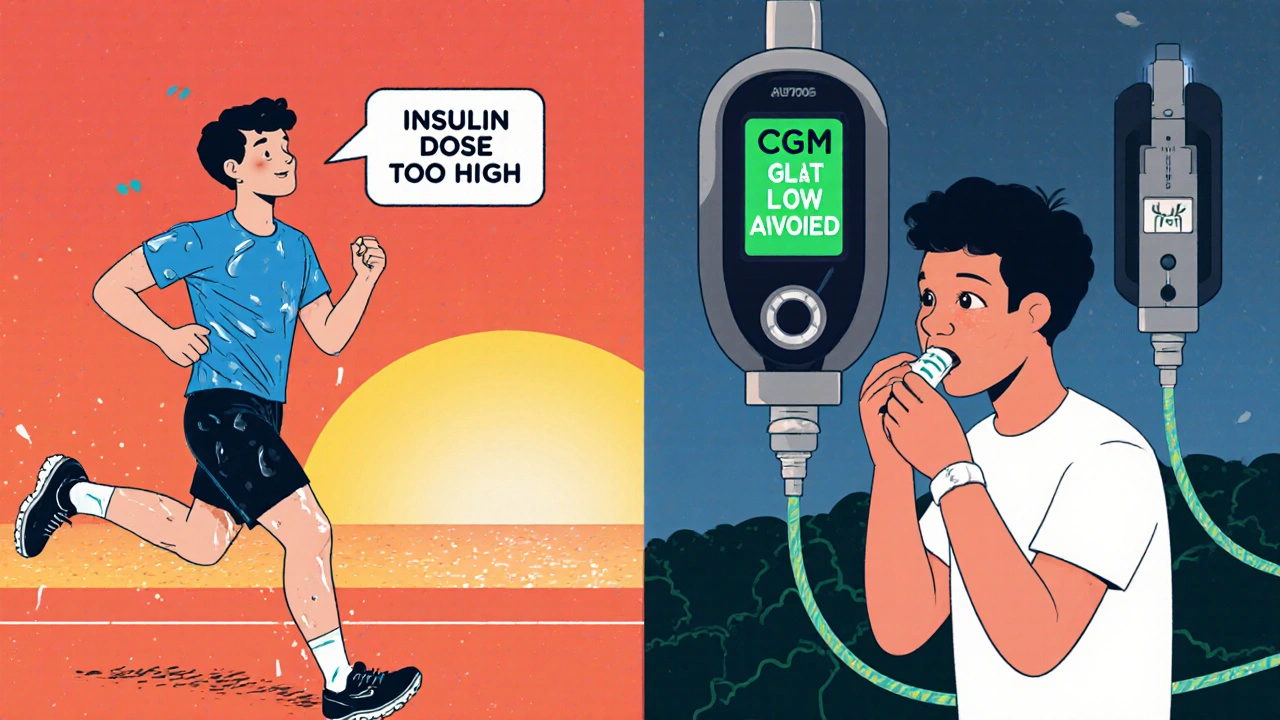

- Exercise without adjustment (9%): A 30-minute walk or bike ride can drop glucose by 30-50 mg/dL if you don’t eat extra carbs or reduce insulin.

- Alcohol: Especially on an empty stomach. It blocks the liver from releasing stored glucose.

- Delayed meals: Waiting too long after taking insulin.

- Insulin timing: Taking rapid-acting insulin too early before eating.

People who use insulin pumps or multiple daily injections are at higher risk because their insulin levels are more precise-and more easily thrown off. Nighttime lows are especially dangerous because you’re asleep. That’s when the body can’t signal you to eat. About 6% of unexpected deaths in young Type 1 diabetics are linked to nighttime hypoglycemia-the so-called "dead-in-bed" syndrome.

How to Treat a Low Blood Sugar Episode

When your glucose hits 70 mg/dL or below, you need fast-acting sugar-immediately. The standard is the 15-15 rule:

- Consume 15 grams of fast-acting carbohydrates.

- Wait 15 minutes.

- Check your blood sugar again.

Good options include:

- 4 glucose tablets (each has about 4g)

- 1/2 cup (4 oz) of regular soda (not diet)

- 1 tablespoon of honey or sugar

- 1 tube of glucose gel

Don’t use chocolate or candy bars. The fat slows down sugar absorption. You need quick, clean glucose. Studies show the 15-15 rule works in 78% of mild to moderate cases. But if you’re too confused to eat, or you’ve passed out, you need help.

That’s where glucagon comes in. Glucagon is a hormone that tells your liver to dump stored glucose into your blood. It’s available as a nasal spray (Zegalogue) or an injection. A 1 mg nasal dose works in under 15 minutes for 94% of people. It’s easy to use-even someone with no medical training can give it. Keep it in your bag, your car, your workplace. If you live alone, teach a neighbor or coworker how to use it.

How to Prevent Hypoglycemia

Prevention is better than treatment. Here’s how to cut your risk:

- Use a CGM: Devices like Dexcom or Freestyle Libre show real-time glucose trends. Set alerts for when you’re dropping toward 70 mg/dL. Studies show CGMs reduce low-blood-sugar time by 35%.

- Check before driving: If your glucose is below 70 mg/dL, eat something and wait 15 minutes. At 50 mg/dL, your reaction time is as slow as someone with a 0.08% blood alcohol level-legally drunk.

- Adjust for exercise: If you’re going to be active for more than 45 minutes, reduce your insulin dose by 20-50% or eat 15-30g of carbs before starting.

- Don’t skip meals: Even if you’re not hungry, eat something. A small snack with protein and carbs can keep you stable.

- Limit alcohol: Never drink on an empty stomach. If you do, eat carbs with it and check your glucose before bed.

- Carry emergency supplies: Always have glucose tabs, a glucagon kit, and a medical ID bracelet.

People who get specialized training-like a 3-hour session with a certified diabetes educator-cut their severe hypoglycemia episodes by 37%. That’s not small. It’s life-changing.

What About Non-Diabetics?

If you don’t have diabetes but keep feeling shaky, dizzy, or faint after meals, you might have reactive hypoglycemia. This happens when your body releases too much insulin after eating, especially carbs. It’s rare-about 1 in 10,000 people-and often follows stomach surgery. Eating smaller, balanced meals with protein and fiber helps. Fasting hypoglycemia-low blood sugar after not eating for hours-is more serious. It can signal liver disease, kidney failure, or an insulinoma. If you’re not diabetic and keep having lows, see a doctor. Don’t assume it’s just "being hungry."

Technology Is Changing the Game

Five years ago, most people relied on fingersticks. Now, CGMs are the norm. But the next leap is predictive tech. New insulin pumps like Tandem Control-IQ and Medtronic’s Guardian 4 can automatically pause insulin delivery when they predict a low is coming. In trials, these systems cut nighttime lows by 44% and reduce total low-glucose time by nearly half.

The FDA approved Dasiglucagon nasal spray in 2023-it’s faster, easier, and more reliable than older injectable glucagon. And research is already moving toward glucose-responsive insulin: a type that turns itself down when blood sugar drops. Early trials show a 62% reduction in hypoglycemia duration.

But tech isn’t magic. Sensor lag can cause false readings-especially during rapid drops. One user reported their CGM showed 98 mg/dL while their actual level was 39 mg/dL. Always confirm with a fingerstick if you feel symptoms that don’t match your monitor.

What to Do If Someone Else Has a Low

You might be the person who saves a life. If someone is confused, sweating, or unconscious:

- If they’re awake and can swallow: Give them 15g of fast-acting sugar. Wait 15 minutes.

- If they’re confused or can’t swallow: Don’t put anything in their mouth. You could choke them.

- If they’re unconscious: Use glucagon nasal spray or injection. Call 911 if they don’t wake up in 15 minutes.

Many people mistake hypoglycemia for drunkenness. Emergency responders in England report that over 30% of hypoglycemia calls are initially misdiagnosed as intoxication. If you’re with someone who seems "drunk" but isn’t drinking, ask: "Have you eaten today?" or "Do you have diabetes?"

Final Thoughts: It’s Manageable

Hypoglycemia isn’t a failure. It’s a signal. It tells you something’s out of balance-and you can fix it. The goal isn’t to never have a low. It’s to know how to respond, how to prevent the worst ones, and how to protect yourself and others.

Carry your glucose tabs. Teach your family how to use glucagon. Set your CGM alerts. Check your blood sugar before bed. Don’t ignore the shakes. Don’t wait for the fog to clear. Act fast. Stay prepared. And remember: every low you prevent is one less trip to the ER, one less scary night, one more day lived with confidence.

15 Comments

King Property

November 29, 2025 at 03:33 AM

You people are ridiculous. If you can't manage your blood sugar, don't have kids. This isn't a lifestyle blog-it's a biological failure. I've been insulin-free since 2012 and I don't need a 2000-word essay to tell me not to skip meals.

Yash Hemrajani

November 29, 2025 at 13:57 PM

Ah yes, the classic 15-15 rule. Because nothing says 'medical science' like eating a tablespoon of sugar like it's a shot of tequila. Meanwhile, in India, we just eat jaggery with peanuts. No drama. No tablets. Just food. But sure, keep your glucose gel in your purse, honey.

Pawittar Singh

December 1, 2025 at 06:48 AM

You got this. Seriously. Every time you check your sugar, you're winning. Even if you mess up-yes, even if you eat chocolate and crash-it's not failure, it's data. 💪 I've been Type 1 for 18 years. I’ve passed out in grocery stores. I’ve cried in parking lots. But I’m still here. And so are you. One glucose tab at a time. 🌞

Josh Evans

December 1, 2025 at 14:28 PM

Honestly this was super helpful. I just got diagnosed last month and I was freaking out. The part about alcohol and liver blocking glucose? Mind blown. I’m gonna start carrying tabs in my wallet. Thanks for not making me feel dumb.

Allison Reed

December 1, 2025 at 15:52 PM

This article is a lifeline. The clarity, the structure, the emphasis on prevention over panic-it’s exactly what the community needs. I’ve shared it with my entire family. Everyone now knows how to use glucagon. That’s not just education. That’s protection.

Jacob Keil

December 2, 2025 at 21:21 PM

the real issue isnt sugar its the system. we were designed to hunt not to carb count. insulin is a modern prison. the body knows. your cgms are just surveillance tools. they want you dependent. look at the pharma profits. its not medicine its control. 🌑

Rosy Wilkens

December 3, 2025 at 14:20 PM

Let me be perfectly clear: this is a manufactured crisis. The CDC, ADA, and Big Pharma have spent billions convincing people they’re all walking time bombs. I’ve never had a low. I eat real food. No tablets. No sprays. No alarms. The only thing broken is your mindset.

Andrea Jones

December 5, 2025 at 10:02 AM

Wait, so you're telling me I can just... *eat* something when I feel shaky? Like, a banana? Not a magic potion? Huh. I thought I was supposed to be terrified of my own body. Thanks for the reality check. 😅

Justina Maynard

December 7, 2025 at 04:42 AM

I read this and immediately texted my ex. He’s Type 1. He never told me he kept glucagon in his glovebox. I felt like a terrible partner. Now I’m ordering three nasal sprays. One for him. One for me. One for my cat. Just in case. 🐱💉

Evelyn Salazar Garcia

December 8, 2025 at 02:08 AM

Why is this even a thing? We used to just eat more. America turned healthy into a medical emergency.

Clay Johnson

December 8, 2025 at 20:45 PM

Glucose is not the enemy. Fear is. The body is not broken. It is adapting. The technology is a crutch. The real treatment is silence. Stop checking. Stop reacting. Let it be.

Jermaine Jordan

December 10, 2025 at 04:03 AM

This isn’t just about blood sugar. This is about dignity. About autonomy. About refusing to be defined by a number on a screen. I’ve stared at my CGM at 3 a.m. and screamed into the void. But I got up. I ate. I lived. And so can you. This isn’t a medical pamphlet. It’s a battle cry.

Chetan Chauhan

December 11, 2025 at 17:43 PM

15-15 rule? LOL. In my village we just drink sugary tea and wait. No tablets. No sprays. No alarms. Also, CGMs are for rich people. I use my tongue. If it tastes sweet, I’m fine. If it tastes like metal, I eat a mango. Works better than your fancy tech.

Phil Thornton

December 13, 2025 at 06:37 AM

I used to think I was just clumsy. Turns out I was having lows. Now I carry gummies. No more falling over at work. Thanks for the life hack. 🙌

Diana Askew

November 28, 2025 at 09:16 AM

I knew it. They're putting something in the water. Why else would everyone suddenly need glucose tabs? I checked my CGM after drinking tap water and it dropped 20 points. They know we're onto them. 🤫