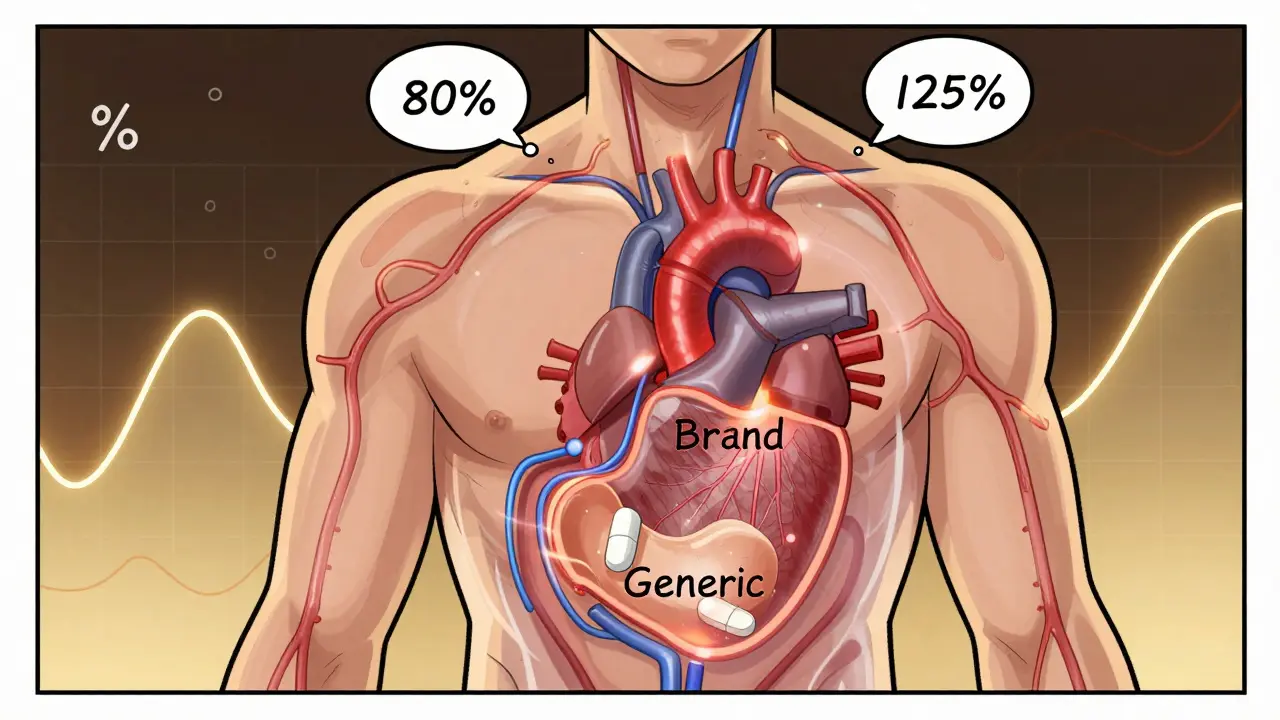

When you pick up a generic pill at the pharmacy, you expect it to work just like the brand-name version. But how do regulators know it actually does? The answer lies in a statistical rule most people have never heard of: the 80-125% rule. It’s not about how much active ingredient is in the pill. It’s not about taste, color, or price. It’s about what happens inside your body after you swallow it.

What the 80-125% Rule Actually Means

The 80-125% rule is the global standard used to prove that a generic drug behaves the same way in your body as the original brand-name drug. It’s not a rule about the amount of drug in the tablet. Many people think it means generics contain only 80% to 125% of the active ingredient - that’s wrong. In reality, both brand and generic drugs must contain 95% to 105% of the labeled amount. The 80-125% range applies to something much more complex: how much of the drug gets into your bloodstream and how fast.This rule is based on two key measurements from clinical studies: AUC (Area Under the Curve) and Cmax (maximum concentration). AUC tells you the total amount of drug your body is exposed to over time. Cmax tells you how quickly the drug reaches its highest level in your blood. These aren’t guesses - they’re measured using blood samples taken from healthy volunteers over hours or days after taking the drug.

Here’s where the math kicks in. Pharmacokinetic data like AUC and Cmax don’t follow a normal bell curve - they follow a log-normal distribution. That means you can’t compare them directly. So scientists take the natural logarithm of each value. On this transformed scale, a 20% difference becomes symmetrical. The 80% and 125% limits on the original scale become -0.2231 and +0.2231 on the log scale. That’s why the rule works mathematically.

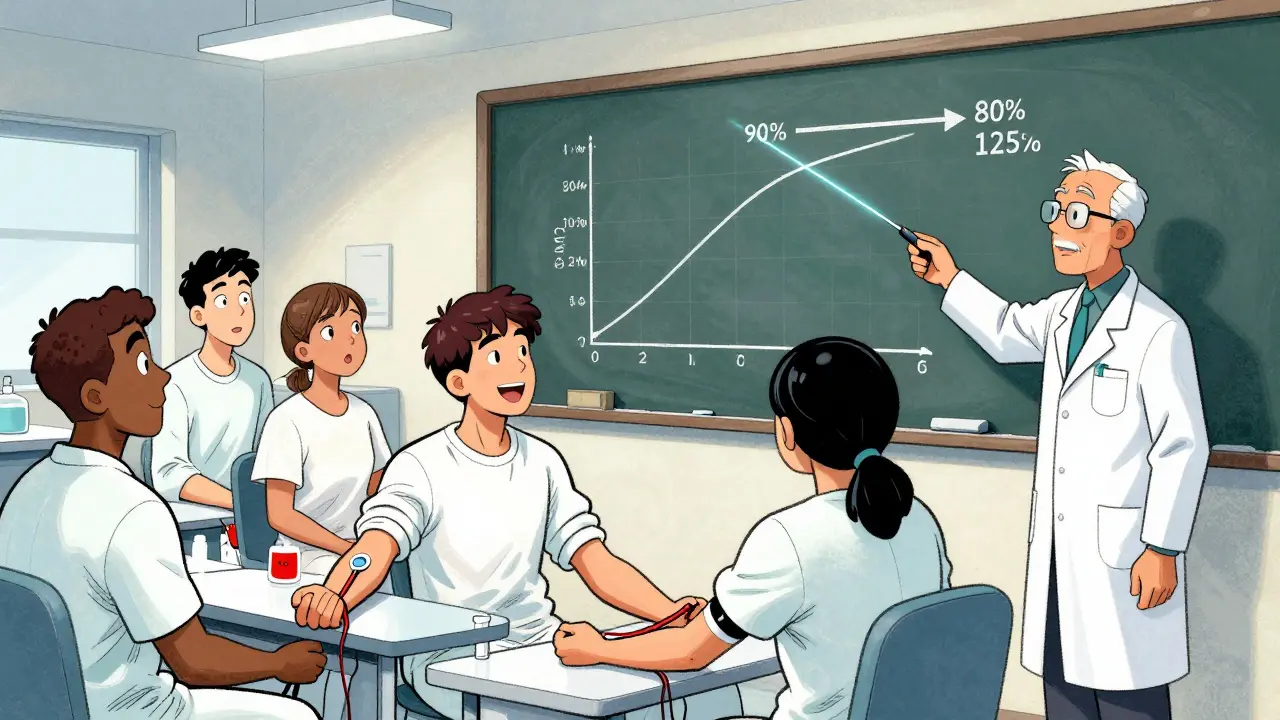

Why a 90% Confidence Interval?

You might wonder why regulators use a 90% confidence interval instead of the more common 95%. It’s a deliberate choice. A 90% CI means that if you repeated the study many times, 90% of the intervals would capture the true ratio of the test to reference drug. This leaves 5% of the risk on each end - 5% chance the test drug is too weak, 5% chance it’s too strong. Together, that’s a 10% total risk of error, which regulators have decided is acceptable for most drugs.For the drug to be approved, the entire 90% confidence interval of the geometric mean ratio must fall between 80% and 125%. If even one point of the interval dips below 80% or rises above 125%, the study fails. It doesn’t matter if the average looks fine - the whole range must fit inside those bounds.

How It’s Tested: The Study Design

Bioequivalence studies aren’t done on patients. They’re done on healthy volunteers, usually between 24 and 36 people. Each volunteer takes both the generic and brand-name drug in a random order, with a washout period in between. This is called a crossover design. It cuts down on individual differences - everyone serves as their own control.After each dose, blood is drawn at regular intervals - often every 15 to 30 minutes at first, then less frequently. These samples are analyzed to calculate AUC and Cmax. The data is log-transformed, and a statistical model calculates the 90% confidence interval. Both AUC and Cmax must pass the 80-125% test. If one fails, the whole study fails. No exceptions.

For drugs that are highly variable - meaning the same person’s response varies a lot from dose to dose - the rules get more flexible. If the within-subject coefficient of variation for Cmax is above 30%, regulators allow something called scaled average bioequivalence (SABE). This lets the acceptance range widen, sometimes up to 69.84% to 143.19%, depending on how variable the drug is. The European Medicines Agency and WHO have clear guidelines for this. The FDA also permits it, but only under strict conditions.

When the Rule Doesn’t Apply

Not all drugs follow the same rules. Some are too dangerous to allow even a small difference. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. Examples include warfarin (a blood thinner), levothyroxine (for thyroid function), and certain anti-seizure medications like phenytoin. For these, regulators demand tighter limits - usually 90% to 111%. That’s because even a 10% difference in exposure can lead to serious side effects or treatment failure.In 2022, the FDA issued draft guidance specifically for NTI drugs, requiring more stringent bioequivalence standards. Some countries, like Germany and Canada, already apply these tighter limits in practice. The American Epilepsy Society has long warned that switching between generics for seizure drugs can trigger breakthrough seizures - not because of the 80-125% rule itself, but because of how it’s applied to drugs that shouldn’t be treated the same way.

Complex drug products also challenge the rule. Inhalers, topical creams, injectables, and extended-release tablets don’t behave like simple pills. Their absorption depends on how they’re made, not just what’s in them. That’s why the FDA launched its Complex Generics Initiative in 2018, investing $35 million a year to develop better testing methods. For some of these, dissolution testing - how fast the drug comes out of the tablet - can replace full bioequivalence studies, if the criteria are met.

Why This Rule Exists

Before the 80-125% rule, regulators used looser standards. In the 1970s, some agencies required 75% of patients to have drug levels within 75-133%. That was messy and inconsistent. The switch to the 80-125% rule in the 1980s was a major upgrade. It was based on expert consensus after the 1986 FDA Bioequivalence Hearing. Experts agreed that differences under 20% in exposure were unlikely to cause clinical harm in most cases.It wasn’t proven by clinical trials. It was chosen because it worked. Since then, over 14,000 generic drugs have been approved in the U.S. alone. Post-marketing surveillance shows that fewer than 0.5% of approved generics have needed label changes due to safety or effectiveness issues. A 2020 FDA analysis of 2,075 generics found no pattern of increased adverse events compared to brand drugs.

That’s why the rule persists. It’s not perfect, but it’s practical. It lets companies bring affordable generics to market without running expensive, years-long clinical trials on every new version. Without it, generics would cost far more - and far fewer people would get them.

Misconceptions and Myths

A 2022 survey by the American Pharmacists Association found that 63% of community pharmacists thought the 80-125% rule meant generics contained less active ingredient. That’s a dangerous misunderstanding. The rule has nothing to do with tablet composition. It’s about how your body handles the drug after you swallow it.Patients often worry. On forums like Drugs.com and Reddit, people ask if their generic is “only 80% as strong.” Pharmacists spend hours explaining the difference between drug content and drug absorption. One Reddit user, u/DragExpert87, summed it up: “Generics contain 95-105% of the label claim, just like brands. The 80-125% is about blood levels, not pills.”

Still, concerns linger. The Institute for Safe Medication Practices logged over 1,200 reports of “therapeutic equivalence concerns” between 2015 and 2022. But only 17% were linked to bioequivalence. Most were due to differences in fillers, coatings, or release mechanisms - not the 80-125% rule itself.

What’s Next for Bioequivalence?

The 80-125% rule isn’t going away. But it’s evolving. The FDA’s 2023-2027 Strategic Plan includes $15 million for research into “model-informed bioequivalence” - using computer simulations to predict how a drug behaves, instead of relying solely on blood samples. This could reduce the need for human studies in the future.Researchers are also looking at pharmacogenomics. What if your genes affect how you metabolize a drug? Could we someday tailor bioequivalence standards to genetic profiles? It’s still early, but by 2030, personalized bioequivalence might be a reality.

For now, the rule remains the backbone of generic drug approval worldwide. The FDA, EMA, WHO, and over 50 other agencies use it. It’s the reason you can buy a month’s supply of blood pressure medicine for $4 instead of $400. It’s not magic. It’s math. And it works.

Does the 80-125% rule mean generic drugs contain less active ingredient?

No. This is a common misunderstanding. Generic drugs must contain 95% to 105% of the labeled amount of active ingredient - the same as brand-name drugs. The 80-125% rule applies to the 90% confidence interval of pharmacokinetic measurements (AUC and Cmax) from clinical studies, not the amount of drug in the tablet.

Why is a 90% confidence interval used instead of 95%?

A 90% confidence interval is used because it allows for a 5% risk of error on each side - 5% chance the generic is too weak, 5% chance it’s too strong. Together, that’s a 10% total risk, which regulators consider acceptable for most drugs. A 95% CI would be too strict and could block safe, effective generics from reaching the market.

Are all generic drugs held to the same 80-125% standard?

No. Most drugs follow the 80-125% rule, but narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin and levothyroxine require tighter limits - usually 90-111%. Highly variable drugs may use scaled bioequivalence, which allows wider ranges based on how much the drug’s effect varies between doses in the same person.

Can a generic drug fail bioequivalence testing even if it looks identical to the brand?

Yes. Two drugs can look, taste, and even dissolve the same, but if the body absorbs them differently - say, one reaches peak concentration faster or slower - the bioequivalence study will fail. The rule is about what happens inside your body, not what’s on the outside of the pill.

How often do generic drugs fail bioequivalence testing?

Failures are rare in practice. Most companies run multiple pilot studies before submitting to regulators. If a study fails, they adjust the formulation and try again. Regulatory agencies reject only about 5-10% of initial submissions. The vast majority of generics that reach the market pass on the first or second attempt.

12 Comments

Lynsey Tyson

December 18, 2025 at 17:15 PM

I used to be super skeptical about generics until I read this

Now I buy them for everything except my thyroid med

My pharmacist actually explained the 80-125% thing to me last year and it made so much sense

It's not about cheating it's about science

And honestly I feel way better knowing there's a whole system behind it

Not just some guy in a lab guessing

Thanks for writing this

Edington Renwick

December 19, 2025 at 13:33 PM

Let me be the first to say this is a government lie

They want you to believe the 80-125% rule is safe

But if you dig into the FDA's own internal memos from 2018 you'll find they admitted the bioequivalence thresholds were chosen because it's cheaper to approve drugs than to test them properly

And don't get me started on how they let generic manufacturers use different fillers that cause reactions

People are getting sick and no one talks about it

This isn't science it's corporate convenience dressed up as math

Allison Pannabekcer

December 20, 2025 at 10:39 AM

There's a lot of nuance here that most people miss

Yes the rule is statistical but it's grounded in real human physiology

And the fact that they adjust for highly variable drugs? That's smart

Not every drug behaves the same way in every body

Some people metabolize things faster because of their liver enzymes or gut flora

That's why SABE exists

It's not a loophole it's a customization

And for NTI drugs? Tighter limits make total sense

Warfarin isn't like ibuprofen

One wrong dose and you're in the ER

So the system isn't broken

It's just complex

And complexity doesn't mean corruption

It means we're trying to account for real human biology

Which is messy

But worth the effort

Sarah McQuillan

December 21, 2025 at 12:44 PM

USA invented this rule and now everyone copies us

Europe? They just copied our math

Canada? They followed our lead

India? They're still trying to catch up

And yet somehow people act like this is some global conspiracy

It's not

It's American innovation keeping medicine affordable

Meanwhile other countries are still stuck in the 1970s

Our FDA didn't just guess

They studied

They debated

They chose the best path

And now the whole world benefits

So yeah the 80-125% rule is American excellence in action

Don't let anyone tell you otherwise

Kitt Eliz

December 22, 2025 at 10:22 AM

OMG THIS IS SO COOL 🤯

Log-normal distributions?? Crossover designs?? SABE??

Y'all didn't tell me bioequivalence was like a sci-fi thriller with blood samples and math!

And the fact that they're using computer models now?? AI predicting drug behavior??

That's next level 🚀

Also shoutout to the FDA for not just saying 'eh close enough'

This is precision medicine before it was cool

Generic drugs aren't cheap because they're lazy

They're cheap because we're smart

And if you're still scared of generics?

Go ask your pharmacist

They know the real tea ☕

Aboobakar Muhammedali

December 22, 2025 at 16:55 PM

Back home in India we don't have this kind of regulation

Some generics are good some are trash

People die because they get bad ones

So when I read this I felt something

Not just knowledge

Hope

That somewhere someone is trying to make sure the medicine works

Not just looks right

Not just costs less

But actually does what it's supposed to

Thank you for writing this

It made me proud

Even if I can't get this kind of quality at home

At least it exists somewhere

anthony funes gomez

December 23, 2025 at 18:29 PM

Statistical power, geometric mean ratios, log-transformed confidence intervals-these are not arbitrary thresholds; they are the product of rigorous pharmacokinetic modeling predicated on the assumption of multiplicative error structures inherent in biological systems.

Yet, the 80–125% range is not empirically derived from clinical outcomes-it is a pragmatic consensus boundary, selected because it correlates-imperfectly-with clinical equivalence in the majority of non-NTI compounds.

And yet, the regulatory inertia persists.

Because to change it would require revalidation of 14,000+ products.

And because the pharmaceutical industry has vested interest in maintaining low barriers to market entry.

So we accept a 10% risk envelope.

As if human biology were a spreadsheet.

It isn't.

And yet.

We proceed.

Laura Hamill

December 25, 2025 at 13:06 PM

They say it's safe but I know the truth

Big Pharma owns the FDA

They let generics in so they can charge you more for the brand later

And those blood tests? They're fake

They just make up the numbers

My cousin took a generic for seizures and had a fit

They said it was 'bioequivalent'

But I know

They're lying to us

And the 80-125% rule? It's just the cover

They don't care if you die

As long as the stock price goes up

Wake up people

It's all a scam

Alana Koerts

December 27, 2025 at 12:16 PM

So what? It's just a rule

Who cares if the CI is 90% or 95%

It's all just corporate jargon to make people feel better about buying cheap pills

And don't get me started on the 'complex generics' initiative

That's just a fancy way of saying 'we can't test these properly so we'll fake it'

Meanwhile real people are getting sick

And you're over here explaining log transforms like it's a TED Talk

Pathetic

Dikshita Mehta

December 27, 2025 at 16:48 PM

This is one of the clearest explanations I've ever read about bioequivalence

Most people think generics are inferior because they're cheaper

But this shows it's the opposite

The science is actually more sophisticated than the brand-name approval process

And the fact that they adjust for variability? That's what real science looks like

Not one-size-fits-all

But tailored to the drug's behavior

Also the NTI exception? Totally right

Warfarin and levothyroxine need tighter control

Because biology doesn't forgive small mistakes

Good job on breaking this down

Even my mom understood it after I shared this

pascal pantel

December 29, 2025 at 06:58 AM

Let's cut through the BS

They call it science but it's just a loophole

80-125%? That's a 25% swing in exposure

That's not equivalence

That's tolerance

And they call it acceptable? Only because they don't want to run 5-year trials on every single generic

Meanwhile patients are getting different responses

And the FDA doesn't track it because they don't have the budget

So we're playing Russian roulette with our meds

And you call this progress?

This isn't innovation

This is negligence dressed up in statistical jargon

Alex Curran

December 17, 2025 at 17:03 PM

The 80-125% rule is one of those quiet miracles of regulatory science that keeps generics affordable without sacrificing safety

Most people think it's about pill content but it's really about how your body handles the drug

Log-normal distributions make this mathematically necessary and honestly it's brilliant

It's not perfect but it's the best balance we've got between cost and clinical safety

And yeah the 90% CI instead of 95%? That's deliberate to avoid blocking viable generics

Too many people panic when they see 80% and think it's half-strength

It's not about quantity it's about absorption kinetics

Pharmacokinetics is wild when you think about it

Same molecule different body response

That's why crossover studies with blood draws are so crucial

One guy's metabolism can turn a good drug into a bad one

And that's why NTI drugs need tighter limits

Warfarin isn't something you want to gamble with

Even a 5% shift can mean clotting or bleeding

Thank god regulators didn't just wing it

This rule has saved millions from overpaying for meds