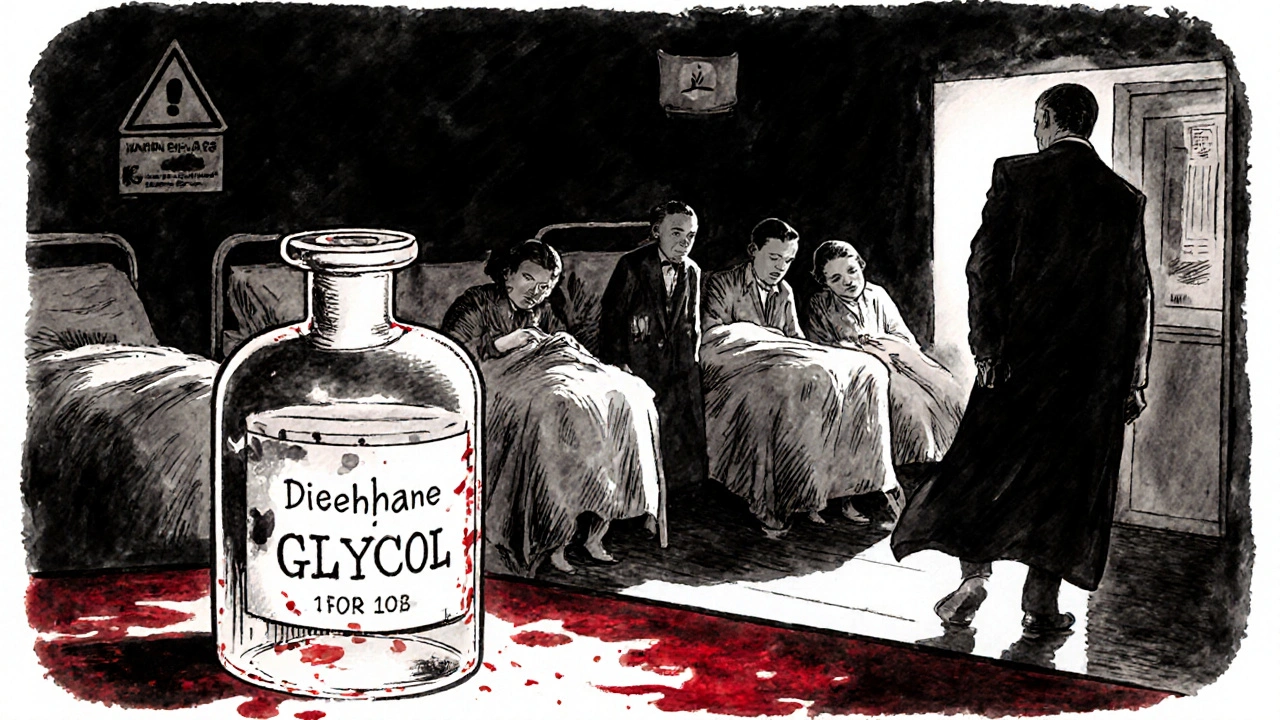

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act didn’t start out as a law about generic drugs. In 1938, it was born out of tragedy. Over 100 people died after taking a liquid antibiotic laced with diethylene glycol - a toxic industrial solvent. At the time, drugmakers didn’t need to prove their products were safe. No testing. No oversight. Just labels and luck. The FD&C Act changed that. It gave the FDA the power to demand safety data before any drug could be sold. But for decades, it did almost nothing to help patients get affordable versions of those drugs.

How Generic Drugs Were Blocked for 45 Years

After 1938, new drugs had to prove safety. Then, in 1962, the Kefauver-Harris Amendments added another rule: drugs had to prove they actually worked. That was a win for public health. But here’s the catch: if you wanted to make a copy of a brand-name drug, you still had to run the same expensive clinical trials - even though the original drug had already been proven safe and effective. That made no sense. Why force a company to repeat 10 years of testing just to sell the same chemical in a different bottle?

Before 1984, only about 19% of prescriptions filled in the U.S. were for generic drugs. And those generics made up just 3% of total drug spending. Why? Because it was too hard, too slow, and too expensive to get them approved. The system was rigged to protect brand-name companies, not patients.

The Hatch-Waxman Amendments: The Game Changer

In 1984, Congress passed the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act - better known as the Hatch-Waxman Amendments. Named after Senator Orrin Hatch and Representative Henry Waxman, this law didn’t rewrite the FD&C Act. It added a new section: 505(j). That section created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. And it changed everything.

Under ANDA, generic manufacturers no longer had to prove safety or effectiveness again. Instead, they had to prove one thing: bioequivalence. That means their version of the drug must deliver the same amount of active ingredient into the bloodstream at the same rate as the brand-name drug. The FDA requires the generic’s absorption levels (measured as Cmax and AUC) to fall within 80-125% of the original. That’s it. No new clinical trials. No new patient studies. Just science.

The law also created the Orange Book - the official list of all approved drugs and their therapeutic equivalence ratings. If a drug is listed there with an “AB” rating, pharmacists can legally substitute the generic without a doctor’s permission. That’s the backbone of generic drug access today.

The Incentive System: Why Companies Fight for the First Spot

Hatch-Waxman didn’t just make generics easier to approve. It gave them a real shot at making money. The first company to file an ANDA and successfully challenge a brand-name patent gets 180 days of exclusive rights to sell their version. No competition. That’s a huge financial reward. It’s why companies like Teva, Sandoz, and Mylan spend millions on legal teams to challenge patents - not to make better drugs, but to be first.

That 180-day window is why you sometimes see two generic versions of the same drug on the market at once - one from the first filer, and another from a competitor who waited. It’s also why some brand-name companies delay generic entry by filing weak, secondary patents - a tactic called “evergreening.” The FDA has cracked down on this, but it still happens.

Patents, Exclusivity, and the Balancing Act

Hatch-Waxman wasn’t just about generics. It also gave brand-name drugmakers a way to recover lost patent time. The FDA approval process can take years. During that time, the patent clock keeps ticking. So the law lets companies extend their patents by up to five years - but not beyond 14 years total from the date the drug hits the market. That’s a compromise: innovation gets protected, but not forever.

Brand-name companies must list all patents covering their drug in the Orange Book. Generic applicants then have to certify whether they believe those patents are invalid, unenforceable, or won’t be infringed. If they challenge a patent and win, they get that 180-day exclusivity. If they don’t challenge it, they have to wait until the patent expires.

This system has saved consumers over $2.2 trillion in the last decade alone. In 2023, 90% of all prescriptions in the U.S. were filled with generics - but those generics made up only 17% of total drug spending. That’s the power of competition.

What Goes Wrong? Enforcement and Compliance

Even with a strong legal framework, things go wrong. The FD&C Act says no drug can be adulterated or misbranded. That means no dirty factories. No fake ingredients. No misleading labels. The FDA inspects generic drug plants - and finds problems. In 2022, 47 warning letters were sent to generic manufacturers. The most common issues? Poor quality control (32%) and data integrity problems (28%).

One company might claim their generic met bioequivalence standards - but if their lab records were backdated or altered, that’s fraud. The FDA can shut down production. The Department of Justice can file criminal charges. Fines for violations can hit over $1.1 million per incident. That’s not just a slap on the wrist. It’s a warning: if you cut corners, you’ll pay.

Complex Drugs and the New Frontier

Not all drugs are easy to copy. Inhalers, injectables, and topical creams are harder to replicate than a simple pill. Their delivery systems matter. The active ingredient might be the same, but if the particle size, spray pattern, or absorption rate is off, the drug won’t work the same way.

That’s why generic entry for complex drugs is 42% slower than for simple pills. The FDA is working on new guidance for these products. Drafts for nasal sprays and eye drops are expected in 2024. The 21st Century Cures Act and the CREATES Act were passed to stop brand-name companies from blocking access to samples needed for testing. These are fixes to a system that’s working - but not perfectly.

What’s Next? Faster Approvals, More Access

Since 2012, the FDA has been funded through the Generic Drug User Fee Amendments (GDUFA). Companies pay fees to support faster reviews. In 2022, 98% of priority ANDAs were approved within 10 months - up from over 30 months in the 1990s. That’s progress.

The Congressional Budget Office estimates that current policies will save the federal government $158 billion on drug spending between 2023 and 2032. That’s money that goes to Medicare, Medicaid, and veterans’ care. It’s not just about cost. It’s about access. A diabetic in rural Ohio shouldn’t have to choose between insulin and rent. Generic drugs make that choice unnecessary.

The FD&C Act started as a safety law. The Hatch-Waxman Amendments turned it into a tool for fairness. It didn’t just allow generics - it created a system where competition drives down prices without sacrificing safety. That’s why it’s still the legal foundation for over 90% of prescriptions in America today.

What is the FD&C Act and how does it relate to generic drugs?

The Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act (FD&C Act) is the 1938 U.S. law that gave the FDA authority to regulate drug safety. While it originally only required proof of safety, the 1984 Hatch-Waxman Amendments added Section 505(j), which created the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. This lets generic manufacturers prove their drugs are bioequivalent to brand-name drugs without repeating clinical trials - making generics possible under the FD&C Act’s framework.

What does ANDA stand for and how does it work?

ANDA stands for Abbreviated New Drug Application. It’s the regulatory pathway generic drug makers use to get FDA approval. Instead of submitting full clinical trial data, they must prove their product has the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand-name drug. They also must show bioequivalence - meaning the generic delivers the same amount of drug into the bloodstream at the same rate, within a 80-125% confidence range.

Why is the Orange Book important for generic drugs?

The Orange Book - officially titled Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations - lists all FDA-approved drugs and their therapeutic equivalence ratings. If a generic drug has an “AB” rating, it means the FDA considers it interchangeable with the brand-name drug. Pharmacists can swap them without asking the doctor. Without the Orange Book, there would be no clear standard for substitution, and generic access would be chaotic.

What is the 180-day exclusivity period for generic drugs?

The first generic company to file an ANDA and successfully challenge a brand-name patent gets 180 days of market exclusivity. During that time, no other generic versions can enter the market. This incentive encourages generic manufacturers to take legal risks and challenge weak or questionable patents. It’s why some generics appear on the market quickly after a patent expires - and why others don’t show up until months later.

Why are some generic drugs still expensive or hard to find?

Some drugs are hard to copy because they’re complex - like inhalers, injectables, or topical creams. Manufacturing them requires precise technology, and the FDA needs more time to evaluate them. Brand-name companies also use tactics like “product hopping” or filing weak patents to delay competition. These delays, combined with low manufacturer interest in low-margin drugs, mean some generics are still scarce or priced higher than expected - even with the Hatch-Waxman system in place.

How does the FDA ensure generic drugs are safe?

The FDA requires generic drugs to meet the same strict standards as brand-name drugs: same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration. They must prove bioequivalence through pharmacokinetic studies. Manufacturing facilities are inspected regularly, and the FDA monitors adverse events. In 2022, 47 warning letters were issued to generic manufacturers for issues like poor quality control and data manipulation - showing the FDA actively enforces compliance.

10 Comments

George Gaitara

November 17, 2025 at 03:48 AM

Actually, the bioequivalence standard of 80–125% is scientifically indefensible. That’s a 45% variance in systemic exposure. If I took a pill that delivered 80% of the intended dose, I’d be clinically underdosed. And if it delivered 125%? Toxic. This isn’t ‘close enough’-it’s a regulatory loophole dressed up as science. The FDA should require 95–105%. Period.

Deepali Singh

November 18, 2025 at 21:08 PM

Interesting how the 180-day exclusivity window creates artificial scarcity. The first filer often doesn’t even lower prices significantly-just monopolizes the market. Then, when the exclusivity expires, the second generic drops prices by 90%. The system incentivizes litigation over accessibility. It’s capitalism with a side of irony.

Sylvia Clarke

November 20, 2025 at 13:44 PM

It’s fascinating how a law designed to prevent another Elixir Sulfanilamide disaster evolved into a sophisticated engine of market competition. The Orange Book? Brilliant. The ANDA pathway? Elegant. The 180-day exclusivity? A necessary evil. But let’s not pretend this system is flawless-complex drugs, patent evergreening, and manufacturing fraud still undermine its promise. We’ve built a cathedral of access… but there are still rats in the basement.

Jennifer Howard

November 22, 2025 at 01:47 AM

While I appreciate the intent of the Hatch-Waxman Amendments, I must emphasize that the FDA's approval process for generics is alarmingly lax. There have been documented cases of substandard manufacturing facilities in India and China supplying American pharmacies. The notion that bioequivalence is sufficient is a dangerous fallacy. Patients deserve more than statistical approximations-they deserve absolute certainty. This is not a consumer electronics product. It is medicine. And medicine must be perfect.

Abdul Mubeen

November 22, 2025 at 11:57 AM

Let’s be honest: the entire generic drug system is a controlled demolition of pharmaceutical sovereignty. The 180-day exclusivity? A distraction. The Orange Book? A propaganda tool. Behind the scenes, the FDA and Big Pharma are in cahoots-allowing just enough generic competition to pacify the public while maintaining pricing control through patent extensions and evergreening. This isn’t reform. It’s theater.

mike tallent

November 24, 2025 at 10:59 AM

Biggest win for everyday people? The fact that a 30-day supply of metformin now costs less than a latte. 💯 I’ve seen grandparents skip doses because they couldn’t afford the brand. Now? They take it like clockwork. Hatch-Waxman didn’t just change the law-it changed lives. And yeah, some generics are sketchy. But the FDA catches most of them. Don’t let a few bad apples ruin the whole orchard.

Joyce Genon

November 26, 2025 at 08:16 AM

Everyone’s acting like this is some kind of triumph, but let’s not forget that the system still allows brand-name companies to game the patent system with absurdly weak secondary patents on inactive ingredients or packaging-delaying generics for years, sometimes even after the original patent expires. And the 180-day exclusivity? It’s not a reward-it’s a perverse incentive to litigate instead of innovate. And don’t get me started on how the FDA’s inspection system is underfunded and overwhelmed-47 warning letters in 2022? That’s not enforcement, that’s triage. We’re letting generic manufacturers cut corners because we’re too lazy to fund proper oversight. And now we’re surprised when someone gets sick from a contaminated batch? Classic.

John Wayne

November 27, 2025 at 19:13 PM

One might argue that the FD&C Act’s evolution into a generic drug framework represents a dilution of scientific rigor in favor of populist economics. The notion that bioequivalence is sufficient to guarantee therapeutic equivalence is a reductionist fallacy. The body is not a test tube. Pharmacokinetic curves do not capture pharmacodynamic outcomes. One should not confuse regulatory convenience with clinical fidelity.

Margo Utomo

November 28, 2025 at 03:15 AM

@George Gaitara - you’re right that 80–125% sounds wild… until you realize that’s the same range the FDA uses for brand-name drugs across different batches. 😏 The brand’s own manufacturing varies more than generics do. And if you’re still worried? Stick with the brand. Nobody’s forcing you to take the $12 version. But millions of people can’t afford the $400 one. So… yeah. I’ll take the math over the moral panic. 🤷♀️

Margo Utomo

November 17, 2025 at 02:18 AM

So basically, the FD&C Act was born from a tragedy, and Hatch-Waxman turned it into a superhero origin story for cheap meds 🦸♀️💊. I used to pay $400 for my asthma inhaler. Now? $12. Same drug. Same results. Just without the corporate markup. Thank you, Congress, for not screwing this up for once. 🙌